The everydayness of ethics in dementia

A long time ago I learned something very important about ethics and dementia. It’s everyday ethics. Actually, I think this is true of all of our lives, that in our day-to-day decisions and encounters ethics is everywhere. Somehow, this is brought out very clearly in connection with dementia. It was through speaking with family carers of people living with dementia that I saw just how obvious this is.

Take Mr and Mrs Carter described in Dementia and Ethics Reconsidered, where he has a diagnosis of vascular dementia and has always been good at do-it-yourself, but she is now aware that he cannot do things as well as he once did. It’s an ethical question for her: should she get people in to do the jobs for her and, if she does, what does she tell him? There were lots of examples like this. Someone else was worried about giving medication to their spouse in case it sedated them too much, but could not manage the person’s behaviour without the medication.

This is what ethics is: it’s about deciding what is right and wrong, what is good or bad. Am I a bad person because I’d rather he was a little sedated than agitated? Have I done the right thing in telling a small lie about the person who came to fix the door? In dementia it can be everywhere and everyday. For family carers, from first thing in the morning until last thing at night, there is the physical and emotional strain of caring; but there’s also the ethical burden of having to decide what is right and wrong and the persistent worry that your loss of temper makes you a bad person.

It is not much better for the person living with dementia, by the way.

· Should I accept a diagnosis or fight against it?

· What provisions should I make for the future?

· Will my wishes be a burden for those who must care for me?

· Am I being fair to those around me?

· If I don’t understand things, what should I do?

Meanwhile, it’s not always easy even for the professionals.

· When should they treat or not treat someone?

· Should they ever break confidences?

· Should they sanction the use of medication concealed in someone’s food?

· If they are doing research, should they tell people if they find something untoward which the person is unaware of?

· Is it right to feed people by tubes if their swallowing is compromised?

Ethics is all everywhere and is everyday.

Let’s reconsider!

The Reconsidering Dementia Series, published by Open University Press, is doing a good job of making us think again. Whether this is about psychotherapy, about training, about neighbourhoods, or whatever, it is good to look at things afresh. What is fresh when it comes to ethics?

Well one thing is the idea that – rather than all becoming skilled at moral philosophy in order to decide what is wrong or right – we respond to situations according to patterns of practice. We build up patterns of behaviour, almost unconscious ways of responding to people and events, which happen naturally.

This doesn’t mean that we don’t have to think about what we do. But a natural way to think, for most of us, is whether what we are doing is coherent. Does this cohere with other things that I do and is it coherent with the important matters that guide my life? If not, I’m likely to be aware of the tweak of conscience: “Wouldn’t I normally do or think this rather than that?”.

This is explained more fully in Dementia and Ethics Reconsidered. But briefly, take the issue of sexuality and intimacy. If a person living with dementia in a care home forms a liaison with another resident, but they are both married to people who still live independently outside the home, what attitude should the staff take? Well, if in other situations they would make the safety of their residents a top priority, they should do this in the current case too. Are they sure that neither person is being hurt, abused, coerced or forced in any way? But they must not forget some of the other important values that guide their lives and the lives of their residents. One the one hand, the importance of the person’s marriage vows must be taken into consideration and the harm that the current relationship might do to the wider family. On the other hand, there should be a recognition that we all benefit from intimacy and from firm friendships based on love. Sociability is part of what makes us human beings. It will take a variety of virtues to weigh these matters up. (Virtues are much discussed in Dementia and Ethics Reconsidered.) But it is the coherence and consistency of these instincts that seem to matter in everyday ethics.

And then there’s the person

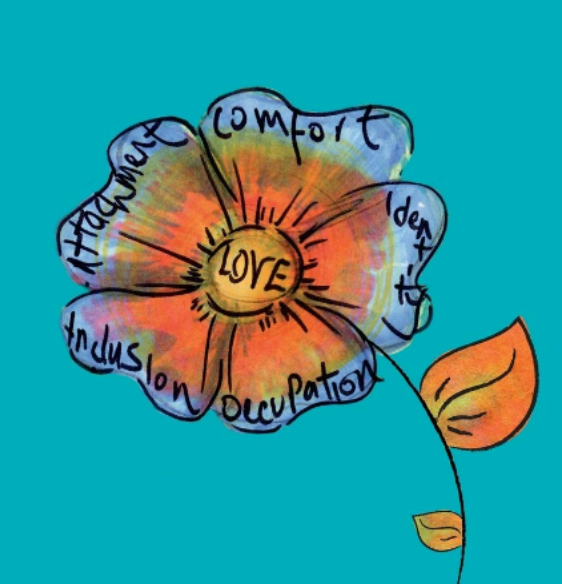

When I was reconsidering ethics in connection with dementia, I couldn’t help thinking again about the work of Tom Kitwood, whose work on person-centred dementia care prompted the whole Reconsidering Dementia Series. Kitwood stressed the nature of the person and wanted us to think about persons as whole people, not just as people with this or that impairment. The key word that comes to my mind when I think of persons in this broader way is the word “situated”. We are all situated in a great variety of fields, which all contribute to us being the people that we are. I have a family, a culture, a history and so on.

Everyday ethics must take into account the reality of life for people, of where we come from, of how we are interconnected and interdependent. The urgent need in dementia is to see the person as a whole and to engage with him or her in a genuine way. In so doing, we are more likely to see the everyday ethical issues as they really are.

Julian C. Hughes was a consultant in old age psychiatry. Having trained in both philosophy and medicine, he was appointed honorary professor of philosophy of ageing at Newcastle

Dementia and Ethics Reconsidered